Institutions Matter: Experiments in Real Life

- >

- Uncategorized

- >

- Institutions Matter: Exp…

We don’t usually think of conducting experiments in social science. What would the mad social scientist do – imprison two groups of people in plastic bubble-biomes and use one as the control group while administering different economic or social policies to the other? Not likely! But, every once in awhile, social science “experiments” happen on their own, and when we are alert enough to recognize them, we can learn a great deal.

A real-life social science experiment in how institutions shape people’s lives has been taking place for the past half-century in North and South Korea. Results in such historical experiments emerge at unpredictable times, so we have to be paying attention. Fortunately, this set of data was hard to miss; it was splashed all over the news and internet – Current TV reporters, Laura Ling and Euna Lee, were arrested on March 17, 2009, for the crime of illegally entering North Korea across its unmarked border with China. Governments and human rights organizations immediately called for the women’s release, but Kim Jong Il’s regime stayed stonily silent. After 3 long months, the journalists were tried and, on June 5th, sentenced to 12 years of hard labor. Let’s examine the bits and pieces of information about life in North Korea that trickled out over the spring and summer and compare them to what we know about life in South Korea. Koreans south of the 38th parallel have a great deal of economic freedom, and those north have none – a difference in institutions that makes “all the difference in the world.”

The words “arrest,” “trial,” and “sentencing” bring us mental images of police powers constrained by individuals’ rights, courtrooms that operate on the presumption of innocence, and sentencing administered by impartial judges. The international human rights organization, Amnesty International, reminds us that Laura Ling and Euna Lee, whether they actually crossed the physical border of North Korea or not, had certainly stepped into another world where we’d have a hard time finding the institutions of justice we take for granted.

“These two foreign journalists were subjected to the failures and shortcomings of the North Korean judicial system: no access to lawyers, no due process, no transparency,” said Roseann Rife, Amnesty International’s Asia-Pacific Deputy Director. “The North Korean judicial and penal systems are more instruments of suppression than of justice.”

Laura Ling and Euna Lee work for California-based Internet broadcaster Current TV in San Francisco. North Korean officials arrested them on 17 March near the Tumen River, which separates North Korea and China.

It is not yet clear whether the two women had crossed the border into North Korea or if they were in China when arrested. The two were investigating human rights abuses of North Korean women.

The journalists had been held separately and in solitary confinement in a “state guest house” near Pyongyang. They had limited consular support and very limited contact with their families after their arrest.

Amnesty International pointed out that prisoners in North Korea were forced to undertake physically demanding work which included farming and stone quarrying, often for 10 hours or more per day, with no rest days.

The organization said that guards beat prisoners suspected of lying, not working fast enough or for forgetting the rules and regulations of the prison. Forms of punishment included forced exercise, sitting without moving for prolonged periods of time and humiliating public criticism.

Prisoners fell ill or died in custody, due to the combination of forced hard labour, inadequate food, beatings, lack of medical care and unhygienic living conditions.

Happily, the American journalists were freed on August 4th after a high profile visit by former president Bill Clinton. The iconic picture of the unusually somber Clinton and North Korean leader, Kim Jung Il, speaks volumes. All this for the illegal act of stepping across an unmarked border? What kind of place is it where punishment seems so disproportionate to the crime? Even as Americans celebrated Ling’s and Lee’s restored freedom, we had to wonder what life must be like for citizens of The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, who are beyond the reach of Bill Clinton’s – indeed, it seems anyone’s -diplomacy.

Happily, the American journalists were freed on August 4th after a high profile visit by former president Bill Clinton. The iconic picture of the unusually somber Clinton and North Korean leader, Kim Jung Il, speaks volumes. All this for the illegal act of stepping across an unmarked border? What kind of place is it where punishment seems so disproportionate to the crime? Even as Americans celebrated Ling’s and Lee’s restored freedom, we had to wonder what life must be like for citizens of The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, who are beyond the reach of Bill Clinton’s – indeed, it seems anyone’s -diplomacy.

Accidental experimental design

If the glimpses of life in North Korea that leaked from the journalists’ story are in some sense “experimental data,” the conditions for this real-life experiment started in ancient history. For millennia, the Korean people have been an extremely homogeneous group and their cultural and biological uniqueness have been maintained into modern times. Centuries of medieval kingdoms ended with the Japanese invasion in 1590. For the next three hundred years, Japan dominated Korea and eventually annexed the country in 1910, but Japanese influence did not significantly dilute the Korean population. That’s the background; the experiment itself began in 1945 when Korea was divided after the Japanese defeat in WWII. The United States and the Soviet Union became trustees of the northern and southern halves of the peninsula as part of a United Nations’ plan that established two new governments: the democratic Republic of Korea (South Korea) and the communist Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea). The effort to create two countries from one people did not go smoothly. Tensions exploded in the 1950 Korean War and continue to loom today as a people who once shared history and culture are separated by the 38th parallel, the world’s most divisive and protected border.This unique history is the foundation for a social science experiment about how institutions impact people’s lives. Here we have a homogeneous people (the United Nations estimates the foreign population in both North and South Korea at well below 1%), who share biology, history, and culture, living in a clearly defined geographic peninsula. The only significant difference is that for the past half century, they have lived under different governmental and economic institutions. Our experimental question asks: The same people, different institutions; do the institutions matter? As you’ll discover, the evidence shouts, “Yes!”

What are institutions?

One of the important contributions made by economic historian Douglass North has been to highlight the importance of institutions in the study of economies and economic change. In his Nobel Prize Lecture, North famously labeled institutions “the rules of the game,” noting that by shaping incentives, institutions influence the decisions individuals make and the ways they interact with other people in society.

“. . . [Institutions are] the humanly devised constraints that structure human interaction. They are made up of formal constraints (rules, laws, constitutions), informal constraints (norms of behavior, conventions, and self imposed codes of conduct), and their enforcement characteristics…Institutions form the incentive structure of a society and . . . in consequence, are the underlying determinant of economic performance.” nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics

The centuries-long debate about the merits of central planning vs. free market economics is fundamentally an argument about which institutions are best for human flourishing and well-being. For many, the demise of the Soviet Union two decades ago provided the uncontested answer to that question, but others remain unconvinced, suggesting that perhaps the problem was that the Soviets didn’t quite “get it right.” Even among those who acknowledge the failure of totally centralized government, the argument about the margins continues. Debate over how much central control is “too much” is a permanent feature of politics in many free market countries, including our own. And finally, while it is true that most industrialized countries embrace the key institutions of market economies and that most centrally-planned communist economies collapsed with the demise of the Soviet Union, a few remain – including North Korea. As the lessons of the Soviet Union fade into memory, comparing the reality of life in North and South Korea offers us another opportunity to sanswer the question of whether economic and governmental institutions matter.

Let’s confine our inquiry to the key institutions of economic freedom found in wealthy developed nations, including:

- the rule of law;

- private property rights;

- open and competitive markets; and

- entrepreneurship and innovation.

Were we to construct a continuum of countries from the strongest to the weakest institutions, you could probably guess that North Korea would be on the “weaker” (least economically free) end of the continuum and South Korea on the “stronger” end (most economically free). But what do “weaker” and “stronger” mean in terms of standard of living, and how significant is the difference in economic freedom to the everyday lives of people in the two Koreas? A closer look at the experimental evidence about each of the institutions will help us to answer those questions.

Let’s start by considering the rule of law, which many modern economists, philosophers, and policy researchers believe to be the single most important institution for securing individual freedom and well-being. Having a strong rule of law means not only that the country has laws; it means that there is an expectation that laws will be administered and enforced in a consistent and impartial manner. Perhaps most significant is that in countries with the rule of law those in government are subject to the law in the same way as the people they govern. The incident of the journalists tells us much about the lack of rule of law in North Korea, a country with a history of arbitrary punishment that did not bode well for Ling and Lee.

South Korea, in stark contrast, ranks near the top of nations for the strength of its rule of law, scoring an impressive 8.33 out of a possible 10 for the “integrity of the legal system” in the Fraser Institute’s Free the World index. Had the journalists trespassed across the South Korean border and been arrested, their trial would likely have garnered little notice by Amnesty International. (See www.freetheworld.com/2008 p. 160.)

The Heritage Foundation, like the Fraser Institute, compiles an index of economic freedom. Of the 179 countries evaluated, South Korea is ranked as a “mostly free” country, while North Korea lags at the very bottom of the list, labeled a “repressed economy”. The index is made up of 10 components, some of which directly measure the institutions we’re trying to compare. For example, the average world score for security of private property rights is 44; South Korea’s 2009 score is 70 and North Korea’s is 5. (See www.heritage.org)

Because North Korea is a communist country, where all production and distribution of goods and services is controlled by the government, it doesn’t even make the bottom of anyone’s list of rankings for “open and competitive market” institutions. But South Korea, labeled “relatively free” in the Fraser Institute’s index, received a score of 6.89 in freedom to trade, a good proxy for the existence of markets. (See www.freetheworld.com/2008 p. 160.)

Finally, let’s look at entrepreneurship and innovation. The World Bank Group publishes the annual “Ease of Doing Business” survey, which gives us a good picture of entrepreneurship. By this time, I hope you’re not surprised that North Korea doesn’t make the list. There are no (legal) private businesses in North Korea; the state controls all production and distribution. South Korea, on the other hand, ranks 19th in the world! (See www.doingbusiness.org/EconomyRankings.) It also consistently ranks high in The Economist Intelligence Unit’s list of most innovative countries – 11th in 2008 – and again, North Korea is a no-show. (See graphics.eiu.com p. 5)

Ok, now you have a general picture of the key institutions: rule of law, private property rights, markets, and entrepreneurship and innovation. Think of that as the experimental set up – the two biomes we imagined at the beginning of this article: North Korea and South Korea. People sharing biology, geography, and culture have been subjected to different institutions. The rankings tell us something about how different those institutions are. The discussion questions that follow will help you make sense of the experimental results. When you finish, you’ll understand why this lesson is entitled “Institutions Matter.” You should also be able to discuss how they matter to people living in the two Koreas and why we should pay attention to the outcome of this ongoing real-world experiment.

Questions for Discussion

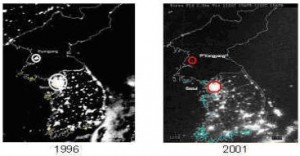

- After comparing institutions in North and South Korea, the next step is to investigate how these differences manifest themselves in the standards of living. Start with these satellite pictures of the two Koreas at night. What do you see – and not see- that offers insights into the standards of living of people in North and South Korea? (Source www.globalsecurity.org/military)

- In addition to the picture in question #1, look at the chart below, which was compiled from World Bank and CIA World Factbook sources. How do you think the standards of living in North and South Korea compare to ours?

Data – 2007 South Korea North Korea population 48.46 million 23.78 million GDP ($US, PPP) $1.335 trillion $40 billion per capita income ($US, PPP) $24, 840 $1,800 (estimate) life expectancy at birth 79 67 fertility rate (births/1000) 1.3 1.9 mortality rate, under 5 (per 1000 live births) 5 55 internet users /1000 people 75.9 0 Sources: World Bank Report and CIA Publication

- If you pay attention to the news, you know that North Korea keeps the world on-edge by refusing to stop nuclear development and by launching missile tests. When we were comparing innovation, it might have occurred to you to protest that North Koreans apparently aren’t stupid if they can develop nuclear technology. You’d have a point. North Korea does seem to be able to invent, to conduct military research, and to develop sophisticated technologies. But remember that we were looking at innovation, which occurs only when invention is translated into consumer goods and services. The photo in question #1 is only one bit of evidence that that transfer isn’t happening in North Korea

- Based on the photo, what would you guess to be the trade-off the Korean government is making to pour resources into military research and development?

- Who is bearing the cost of that choice?

- In the 2008 election campaign, candidate John McCain asserted that North Koreans are shorter than South Koreans. Pundits on both sides scrambled to verify or undermine his claim, which turned out to be accurate.

Height statistics for 1,075 North Korean defectors ranging in age from 20 to 39 were compiled by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention, while equivalent South Korean statistics were obtained by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. Both organizations collected the information in 2005. . . .

North Korea South Korea Males 165.6cm (5′ 4.5″) 172.5cm (5′ 8.5″) Females 154.9cm (5′ 1.0″) 159.1cm (5′ 3.5″) Beyond being interesting, it’s pertinent to our “experiment” because demographic researchers have discovered that the average height of a population is a good indicator of how well people live – specifically, whether they are receiving adequate nutrition to grow to their genetic potential.

. . . South Korean anthropologists who measured North Korean refugees here in Yanji, a city 15 miles from the North Korean border, found that most of the teenage boys stood less than 5 feet tall and weighed less than 100 pounds. In contrast, the average 17-year-old South Korean boy is 5-feet-8, slightly shorter than an American boy of the same age.

The height disparities are stunning because Koreans were more or less the same size – if anything, people in the North were slightly taller – until the abrupt partitioning of the country after World War II.

. . . Foreigners who get the chance to visit North Korea – perhaps the most isolated country in the world – are often confused about the age of children. Nine-year-olds are mistaken for kindergartners and soldiers for Boy Scouts.

. . . The North Korean military had so much difficulty finding tall-enough recruits that it had to revoke its minimum height requirement of 5-feet-3. Many soldiers today are less than 5 feet tall, defectors say. . .

The issue of IQ is sufficiently sensitive that the South Korean anthropologists studying refugee children in China have almost entirely avoided mentioning it in their published work. But they say it is a major unspoken worry for South Koreans, who fear that they could inherit the burden of a seriously impaired generation if Korea is reunified.

“This is our nightmare,” anthropologist Chung said. “We don’t want to get into racial stereotyping or stigmatize North Koreans in any way. But we also worry about what happens if we are living together and we have this generation that was not well-fed and well-educated.” www.dprkstudies.org

Based on the article, write 2 generalizations about the impact of institutions on the well-being of Koreans.

- Anthony Kim, Policy Analyst for The Center for International Trade and Economics, defines economic freedom as

“. . . individuals’ basic economic rights to work, produce, save, and consume without the state’s intimidation and infringement. It encompasses the freedom to engage in entrepreneurial activities, having choices in education and health care, fair taxation, and just treatment by the courts under the rule of law.”

He goes on to assert that

“. . . It is not surprising to see that seven of the 10 countries identified as “the most systematic human rights violators” (North Korea, Burma, Iran, Syria, Zimbabwe, Cuba, and Belarus) by the State Department’s human rights report are “repressed” economies. “

Kim then quotes both former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Nobel economist Friedrich Hayek in defense of the main argument of his 2008 article, “Economic Freedom Underpins Human Rights and Democratic Governance”:

In her preface to the Department of State’s recently published Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2007, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice wrote: “These values [liberty, dignity, and rights] are the basic endowments of all human beings, and the surest way to protect and preserve them is through effective, lawful, democratic governance.”

. . . Friedrich Hayek once observed, “To be controlled in our economic pursuits means to be controlled in everything.” Hayek’s observation on economic freedom is based on the truth that each person is a free and responsible being with an inalienable dignity and fundamental human rights that should come first in any political system. www.heritage.org

- Based on what you’ve learned in this lesson, write an institutional definition of “economic freedom.”

- Do the data you’ve examined in this lesson support or undermine Kim’s main argument? Explain.

- From your knowledge of current events and/or world history, identify 3 other real-world situations we might study as experiments in whether and how institutions matter in people’s lives.

- (Optional) What are the implications of the Korea comparisons for the debate in our country over the appropriate role of government in health care, business failures, and other areas of the economy?

Teacher Guide

- After comparing institutions in North and South Korea, the next step is to investigate how these differences manifest themselves in standards of living. Start with these satellite pictures of the two Koreas at night. What do you see – and not see- that offers insights into the standards of living of people in North and South Korea?It is important that students become familiar with the location of the Korean peninsula on a map as well as the border division between North and South Korea (the 38th parallel) in order to understand the significance of the images. Use a classroom map or the following link to clarify the location. history.acadiau.caThe satellite picture testifies to the expansion of South Korea’s infrastructure from 1996 – 2001. In stark contrast, North Korea remains dark, even in the capital city of Pyongyang, an indication of a severely limited infrastructure

- In addition to the picture in question #1, look at the chart below, which was compiled from World Bank and CIA World Factbook sources. How do you think the standards of living in North and South Koreans compare to ours? Answer will vary. Below are some conclusions that can be drawn from the data include: In a relatively similar geographical region, the population of South Korea is approximately twice as large as the population of North Korea.North Korea’s negligible GDP is in the billions while South Korea has an economy about 1/10th the size of the U.S. GDP divided by population is gives a measure of standard of living. The difference between these two countries is extraordinary. South Koreans live an average 12 years longer than their northern neighbors. While North Korea’s citizens meet the global definition of abject poverty – life on under $1.50 a day, South Korean’s enjoy a per capita income that is approximately half that of the United States.

While a greater number of children are born to households in North Korea, those living beyond the age of five are far fewer.While the majority of South Koreans are Internet users, North Korean citizens have no access to this tool that has become a modern day convenience for learning, shopping and communicating.

- If you pay attention to the news, you know that North Korea keeps the world on-edge by refusing to stop nuclear development and by launching missile tests. When we were comparing innovation, it might have occurred to you to protest that North Koreans apparently aren’t stupid if they can develop nuclear technology. You’d have a point. North Korea does seem to be able to invent, to conduct military research, and to develop sophisticated technologies. But remember that we were looking at innovation, which occurs only when invention is translated into consumer goods and services. The photo in question #1 is only one bit of evidence that that transfer isn’t happening in North Korea.

- Based on the photo, what would you guess to be the trade-off the Korean government is making to pour resources into military research and development?

- Who is bearing the cost of that choice?

Answers will vary. Below are some conclusions that can be supported by the data:

Some trade-offs that the North Korean government is making in order to fund the military powerhouse include the building of homes, highways, schools, factories and everyday consumer goods and services that we know and take for granted. The telling picture of the darkness at night lets us imagine the rudimentary conditions in which people live. In contrast, South Korea is an industrialized nation and advanced economy. Not only is the capital city of Seoul well lit but the entire nation is energized by electricity.

In a communist regime, the three basic questions of what to produce, how to produce it and for whom to produce are answered by the government. Kim Jung Il’s leading party chooses to channel the resources of the country (the land, human resources, capital resources and technology) toward building military might. While many individuals are trained as soldiers, others are assigned to jobs involved in building weaponry and nuclear technology.

The tradeoffs involved are many including the freedom of individuals to choose their work, to own property, to profit from innovation, and to be part of an economy that allocates resources by a price mechanism. This is a formal way of describing a world of daily comforts familiar to people living in the developed world: schools, shopping centers that sell a variety of goods and services, enough food, clothing and shelter to meet the needs of the population, etc.

- In the 2008 election campaign, candidate John McCain asserted that North Koreans are shorter than South Koreans. Pundits on both sides scrambled to verify or undermine his claim, which turned out to be accurate.Based on the article, write 2 generalizations about the impact of institutions on the well-being of Koreans. Answers will vary. Below are some conclusions that can be drawn from the article. The 2.5 inch difference in female height and 4 inch difference in male height is indicative of the differing conditions under which Koreans live. Malnutrition and limited medical care have literally stunted the growth and health of the current generations of people and will likely affect the health of the next generations as well unless conditions improve. A lack of open and competitive markets reduces options of varieties of food, medicine and other choices of goods and services that support health and well-being.A lack of private property rights reduces opportunities for households to farm their own land at the least and to use property as collateral for purposes of loans to start businesses. Individual opportunity for success is nonexistent for the North Koreans who appear to barely survive.Without a rule of law that protects individuals, a North Korean cannot choose to opt out of the military life to protect himself or his family. The destiny, health and wealth of the population is determined by a regime that serves the whims of an eccentric and unpredictable leader.

- Anthony Kim, Policy Analyst for The Center for International Trade and Economics, defines economic freedom as

“. . . individuals’ basic economic rights to work, produce, save, and consume without the state’s intimidation and infringement. It encompasses the freedom to engage in entrepreneurial activities, having choices in education and health care, fair taxation, and just treatment by the courts under the rule of law.”

Based on what you’ve learned in this lesson, write an institutional definition of “economic freedom.”

Do the data you’ve examined in this lesson support or undermine Kim’s main argument? Explain. Answers will vary. Below are some conclusions that are supported by the article.

Economic freedom exists when people have rights to ownership of property and their rights are protected by a rule of law. Competitive markets exist and trade is open. Innovation thrives as a result of shared technology. Individuals are free to pursue personal interests.

Anthony Kim points out that the seven nations known for the poorest treatment of individual freedom and human rights are the nations of the world that are most repressed. He supports the contention that institutions that provide economic freedom are necessary for economic growth and individual well-being.

Some of the data that supports this assertion for North Korea includes the arbitrary judicial system described in the story of the arrest of the journalists, the low economic freedom scores from the Fraser and Heritage rankings and the malnutrition indicated by the height statistics article.

Some of the data that provides evidence of South Korea’s prosperity includes the well-lit night time satellite photograph indicating a flourishing economy, life expectancy that is equivalent to other highly industrialized nations, and the high rankings in the institutions of economic freedom.

- From your knowledge of current events and/or world history, identify 3 other real-world situations we might study as experiments in whether and how institutions matter in people’s lives. Possible answer include:

- East and West Germany before and after the fall of the Berlin wall

- Venezuela before and after Hugo Chavez became President

- North and South Vietnam before and after the Vietnam War

- Cuba before and after Castro

- (Optional) What are the implications of the Korea comparisons for the debate in our country over the appropriate role of government in health care, business failures, and other areas of the economy? Answers will vary but should demonstrate students’ awareness that countries with institutions ranked on the weaker end of the scale of economic freedom have lower standards of living than those on the stronger end of the spectrum. Students should be able to make connections between the evidence emerging from “experiments” like the two Koreas and current debates over the role of government in our economy. That evidence is certainly pertinent to questions that Americans are debating today, such as: “How much should government be involved in providing health care, in regulating banking, or in shoring up troubled industries?”

Welcome: 2020-21 FTE Student Ambassadors

This year, FTE is welcoming thirty-seven student ambassadors who are committed to sharing the economic way of thinking. FTE Ambassadors…

Webinar: The Economic Implications of COVID-19: An Update

On Wednesday, June 10 at 6:00 PM ET/ 3:00 PM PT, Professor Scott Baier, Chair of the Economics Department at…

Webinar: This Is Your Brain On Numbers: Data, Statistics and COVID-19

On Wednesday, May 27 at 3:00 PM PT/ 6:00 PM ET, FTE will present a webinar titled This Is Your…