Historical Overview (2012 update)

- >

- Teachers

- >

- Teacher Resources

- >

- Lesson Plans

- >

- Protected: Is Capitalism Good for the Poor?

- >

- Historical Overview (2012 upda…

A Long-term Economic Perspective on Recent Human Progress

by Gary M. Walton

Professor Emeritus of Economics,

University of California, Davis and President, Foundation for Teaching Economics

download:Economic Perspective of Recent Human Progress (2012 revision)

Lectures (flash video of ppt with voice over) re: History of the Masses:

-

A Brief History of Human Progress (16 min.)

-

Laying the Cards on the Table (14 min.)

History of the Masses

The year 1750 does not usually evoke images of great prosperity or of revolutionary progress, but in fact the mid-eighteenth century was an historical turning point of economic advance. Organizational and technological changes in that period allowed growing numbers of people to move from mere subsistence activities to thoughts and actions that furthered economic, political and social progress. This monumental turning point in human existence is often missed because of the way we perceive the past.

It is an interesting exercise to reflect on an historical episode, perhaps from the Bible, or from Shakespeare, or some Hollywood epic. For most of us, the stories we recall are about great people, or great episodes; tales of love, war, religion, and other dramas of the human experience. Kings, heroes, or religious leaders…in castles, battle fields, or cathedrals…engaging armies in battles, or discovering inventions, or new worlds — readily come to mind. Glorifying the past is a natural instinct.1

There were so called golden ages, like Ancient Greece, the Roman Era, China’s Sung Dynasty, and other periods and places where small fractions of societies lived in splendor and reasonable comfort, and when small portions of the population sometimes rose above levels of meager subsistence (for select accounts see Murray, 2003). But such periods of improvement were never durably sustained.2 Taking a long, broad view, the lives of almost all of our distant ancestors were utterly wretched. Except for the fortunate few, humans everywhere lived in abysmal squalor. To capture the magnitude of this deprivation and sheer length of the road out of poverty, consider this time capsule summary of humanity from Douglass C. North’s 1993 Nobel address:

Let us represent the human experience to date as a 24-hour clock in which the beginning consists of the time (apparently in Africa between 4 and 5 million years ago) when humans became separate from other primates. Then the beginning of so-called civilization occurs with the development of agriculture and permanent settlement in about 8000 B.C. in the Fertile Crescent – in the last three or four minutes of the clock (my emphasis). For the other 23 hours and 56 or 57 minutes, humans remained hunters and gatherers, and while population grew, it did so at a very slow pace.

Now if we make a new 24-hour clock for the time of civilization – the 10,000 years from development of agriculture to the present – the pace of change appears to be very slow for the first 12 hours.…Historical demographers speculate that the rate of population growth may have doubled as compared to the previous era but still was very slow. The pace of change accelerates in the past 5,000 years with the rise and then decline of economies and civilization. Population may have grown from about 300 million at the time of Christ to about 800 million by 1750 – a substantial acceleration as compared to earlier rates of growth. The last 250 years – just 35 minutes on our new 24-hour clock (my emphasis) – are the era of modern economic growth, accompanied by a population explosion that now puts world population in excess of 5 billion (1993).

If we focus on the last 250 years, we see that growth was largely restricted to Western Europe and the overseas extensions of Britain for 200 of those 250 years (North, 1993).3

Any brief explanation of the major forces and events lifting larger and larger portions of the world’s population to levels of good health and decent material comfort suggests a degree of presumption that even a Cheshire cat’s grin could not hide. While acknowledging many problematic issues of measurement and interpretation, we proceed without apology, directly and selectively to the historical evidence. Long-term measures of population size, length of life, infant mortality, body heights and weights, income per person, and many other such indicators of well being, whatever the quibbles over exactness, are perfectly clear. So are the geographic and national identities of the places inventions and improvements came from and where declines of poverty started and spread.

The Decline of Poverty: Where and When

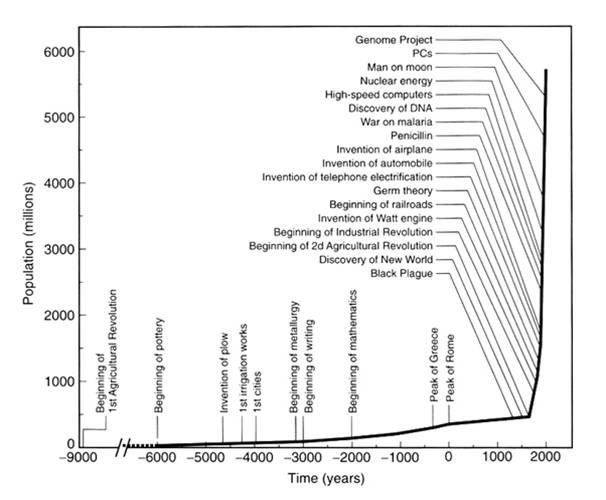

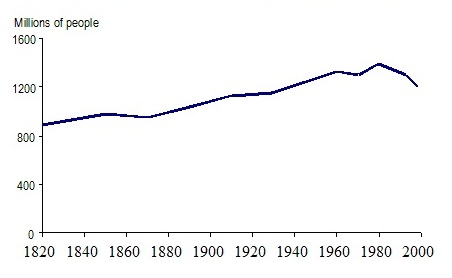

Figure 1 shows world population over the past ten thousand years, along with noteworthy inventions, discoveries, and events. The graph conveys a literal explosion of the world’s population in the mid-eighteenth century. Shortly before the United States won its independence from Britain, the geographical line bolts upward like a rocket, recently powering past seven billion humans alive on Earth. Advances in food production from new technologies, commonly labeled the second Agricultural Revolution, and from the utilization of new resources (e.g., settlements in the New World) coincide with this population explosion. Also noteworthy is the intense acceleration in the pace of vital discoveries. Before 1600, centuries elapsed between vital discoveries. Improvements and the spread of the use of the plow, for example, first introduced in the Mesopotamian Valley around 4000 B.C., changed very little over the next 5000 years. Contrast this with air travel. The first successful motor-driven flight occurred in 1903 by the Wright Brothers. In 1969, a mere sixty-six years later, Neil Armstrong became the first man to step foot on the moon.4

Figure 1. World Population and Major Inventions and Advances in Knowledge

Source: Fogel, 1999

Before 1750, chronic hunger and malnutrition, disease, illness, and early death were the norm, and it was not just the masses who ate poorly; as Nobel Laureate Robert Fogel (1999) reports:

Even the English peerage, with all its wealth, had a diet during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that was deleterious to health. Although abundant in calories and proteins, aristocratic diets were deficient in some nutrients and included large quantities of toxic substances, especially alcoholic beverages and salt. (p. 3)

For most people, poor diet was not a matter of bad choices, it was the absence of choices, the fact of scarcity. Exceedingly poor diets and chronic malnutrition were the norm because food production seldom rose above basic life-sustaining levels. Meager yields severely limited energy for all kinds of pursuits, including production. Most people were caught in a food-energy trap, and low food supplies and inadequate diets were accompanied by high rates of disease and low rates of resistance.5 Remedies from known medical practices were almost nil.

The maladies of malnourishment and widespread disease are revealed in evidence on height and weight. Table 1 shows average final height of men at maturity from economically advanced nations with men gaining four to five inches over two hundred years. Today the average American adult man stands five inches taller than mid-eighteenth century Englishmen. The average Dutchman, the world’s tallest, stands seven inches taller. A typical Englishman in 1750 weighed around 130 pounds, an average Frenchman about 110, compared to about 175 for U.S. males today (Fogel 1994, 2004). It is startling to see the suits of armor in the Tower of London that were worn for ancient wars; they vividly remind us of how small people of long ago really were.

Table 1

Average Height of Men at Maturity in Centimeters

| Great Britain | Sweden | France | |

| 1750-75 | 166 | 168 | |

| 1800-25 (1775-1800) | 168 | 167 | (166) |

| 1850-75 | 169 | 170 | 165 |

| 1950-75 | 175 | 178 | 176 |

Source: Derived from Fogel, 2004, Table 1.4, p. 13.

The second Agricultural Revolution beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, and the Industrial Revolution which soon followed (first in England, then France, the U.S. and other Western countries), initiated and sustained the population explosion, lifting birth rates and lowering death rates. Table 2 summarizes research findings on life expectancy at birth for various nations, places, and times. This and other empirical evidence (Preston, 1995) reveal that for the world as a whole, it took thousands of years for life expectancy at birth to rise from the low 20s to around 30 years in the mid-18th century. Leading the breakaway from a past of early death and malnutrition, poor diet, chronic disease (e.g., chronic diarrhea; see Fogel 1994), and low energy were the nations of Western Europe. From Table 2 we see that by 1800, life expectancy in France was just under 30 years, and in Great Britain about 36, levels that China and India had not reached 100 years later. By 1950, life expectancy in England and France was in the high 60s, while in India and China it was only about 40.

Table 2. Years of Life Expectancy at Birth

| Place |

Middle Ages

|

Select Years

|

1950-55

|

1975-80

|

2002

|

2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sources: Lee and Feng (1999); Peterson (1995); Wrigley and Schofield (1981, 529); World Resources Institute (1998); UNDP (2002), http://hdr.undp.org/statistics/data/indic/indic_1_1_1.html, UNDP (2010) | ||||||

| France |

~30 (1800)

|

66

|

74

|

79

|

82 | |

| United Kingdom |

20-30

|

36 (1799-1803)

|

69

|

73

|

78

|

80 |

| India |

25 (1901-11)

|

39

|

53

|

64

|

64 | |

| China |

25-35 (1929-31)

|

41

|

65

|

71

|

76 | |

| Africa |

38

|

48

|

50

|

53 | ||

| World |

20-30

|

46

|

60

|

67

|

69 | |

When life expectancy data are adjusted for quality by subtracting years of ill health (weighted by severity), “healthy-active life expectancy” indexes reveal years totaling 70, 62, and 53 in the U. S., China, and India respectively in 1997-99 (World Health Report, 2000). These “quality life spans” are substantially more than these countries’ total life expectancies fifty to one hundred years ago.

In the period before 1750, surviving childhood was problematic. Infant mortality was high everywhere; depending on time and location, between 20 and 25 percent or more of babies died before their first birthday. By the early 1800s, infant mortality in France, and probably England, had dipped below the 20 percent level, rates not reached in China and India and other low income developing nations until the 1950s. For Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand, this rate is now under one percent, but remains at 4 percent in China, 6 percent in India, and 9 percent in Africa (World Resources Institute 1999 and UNDP 2000).

Accompanying the declines in infant mortality were striking declines in maternal mortality. For example, U.S. data show infant rates falling from 100 to 7 per 1000 live births (1915 to 1996), with maternal rates plummeting from 220 to 7.6 per 100,000 live births (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999). The high losses of infants and mothers in birth reflect more than just lives lost. They also reflect more pregnancy time over a woman’s life and more time futilely spent in caring for children who died before their first birthday, both time uses implying production losses.

Tables 3 and 4 provide another long-term perspective on the escape from poverty and early death, in the form of evidence on real income per person, albeit very inexact, for periods long ago. The gradual rise of real income over the past one thousand years was led by Europe. By 1700, Europe had broken into a clear lead, rising above the level of per capita income it shared earlier at lower levels with China, which was the most advanced empire/region, circa 1000.

Table 3. Real Gross Domestic Product Per Capita (1990 $)

|

Area

|

1000

|

1500

|

1700

|

1820

|

1900

|

1952

|

2003

|

2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sources: Development Centre Studies The World Economy: Historical Statistics, Maddison 2003. World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2003 AD, Maddison, 2007, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison and http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm for 2008 data. |

||||||||

|

Western

Europe |

$427

|

$772

|

$977

|

$1,202

|

$2,892

|

$4,963

|

$19,912

|

21,672 |

|

USA

|

527

|

1,257

|

4,091

|

10,316

|

29,037

|

31.178 | ||

|

India

|

550

|

533

|

599

|

629

|

2,160

|

2,975 | ||

|

China

|

450

|

600

|

600

|

600

|

545

|

537

|

4,609

|

6.725 |

|

Africa

|

425

|

414

|

421

|

420

|

601

|

928

|

1,549

|

1,780 |

|

World

|

450

|

566

|

615

|

667

|

1,262

|

2,260

|

6,477

|

7,614 |

While the rest of the world slept, and changed little economically, Europe and England’s colonies in America advanced. By the early 1800’s, the United States had pushed ahead of Europe, and by the mid 1900’s, citizens of the U.S. enjoyed incomes well above those of Europeans and many multiples above people living elsewhere. The real impact of regional differences in economic growth is apparent when we realize that the poor nations of today – such as Zaire, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Bangladesh – have per capita income levels comparable to those in Europe 500 to 1000 years ago. Even now, they have not attained levels of well-being experienced by western peoples at the time of the American Revolution (see Table 4).

Table 4. GDP Per Capita Then and Now – 1990 $

| 1820 | 1870 | 1900 | 1950 | 1973 | 2003 | 2008 | |

| Western European Countries | |||||||

| Austria | 1,218 | 1,863 | 2,882 | 3,706 | 11,235 | 21,232 | 24.131 |

| Belgium | 1,319 | 2,692 | 3,731 | 5,462 | 12,170 | 21,205 | 23,655 |

| Denmark | 1,274 | 2,003 | 3,017 | 6,943 | 13,945 | 23,133 | 24.621 |

| Finland | 781 | 1,140 | 1,668 | 4,253 | 11,085 | 20,511 | 24.344 |

| France | 1,135 | 1,876 | 2,876 | 5,271 | 13,114 | 21,861 | 22,223 |

| Germany | 1,077 | 1,839 | 2,985 | 3,881 | 11,966 | 19,144 | 20,801 |

| Italy | 1,117 | 1,499 | 1,785 | 3,502 | 10,634 | 19,150 | 19,909 |

| Netherlands | 1,838 | 2,757 | 3,424 | 5,996 | 13,081 | 21,479 | 24,695 |

| Norway | 801 | 1,360 | 1,877 | 5,430 | 11,324 | 26,033 | 28,500 |

| Sweden | 1,198 | 1,662 | 2,561 | 6,739 | 13,494 | 21,555 | 24,409 |

| Switzerland | 1,090 | 2,102 | 3,833 | 9,064 | 18,204 | 22,242 | 25,104 |

| United Kingdom | 1,706 | 3,190 | 4,492 | 6,939 | 12,025 | 21,310 | 23,742 |

| Western Offshoots | |||||||

| Australia | 518 | 3,273 | 4,013 | 7,412 | 12,878 | 23,287 | 25,301 |

| New Zealand | 400 | 3,100 | 4,298 | 8,456 | 12,424 | 17,564 | 18,653 |

| Canada | 904 | 1,695 | 2,911 | 7,291 | 13,838 | 23,236 | 25,267 |

| United States | 1,257 | 2,445 | 4,091 | 9,561 | 16,689 | 29,037 | 31,178 |

| Selected Asian Countries | |||||||

| China | 600 | 530 | 545 | 439 | 838 | 4,609 | 6,725 |

| India | 533 | 533 | 599 | 619 | 853 | 2,160 | 2,975 |

| Bangladesh | 540 | 497 | 939 | 1,146 | |||

| Burma | 504 | 504 | 396 | 628 | 1,896 | 3,104 | |

| Pakistan | 643 | 954 | 1,881 | 2,239 | |||

| Selected African Countries | |||||||

| Côte d’Ivoire | 1,041 | 1,899 | 1,230 | 1,094 | |||

| Egypt | 475 | 649 | 910 | 1,294 | 3,034 | 3,534 | |

| Eritrea & Ethiopia | 390 | 630 | 595 | 805 | |||

| Ghana | 439 | 1,122 | 1,397 | 1,360 | 1,568 | ||

| Kenya | 651 | 970 | 998 | 1,110 | |||

| Nigeria | 753 | 1,388 | 1,349 | 1,468 | |||

| Tanzania | 424 | 593 | 610 | 744 | |||

| Zaire | 570 | 819 | 212 | 249 | |||

Sources: Development Centre Studies The World Economy: Historical Statistics, Maddison 2003.

World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2003 AD, Maddison, 2007, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/ and http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm for 2008 data

Educational gains have also been dramatic in the past century (Appendix 1). Measured in terms of formal years of education of adults, education levels have more than doubled world-wide and nearly quadrupled in developing nations (1950-2010).

An Institutional Road-Map to Plenty

From these per capita income estimates and other evidence, and from North’s fascinating time capsule summary of human existence, it is clear that the road out of poverty is new. It has been traveled by few societies: Western Europe; the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (Britain’s offshoots); Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore; and few others. What steps did Western Europe and its “offshoots” take to lead humanity along the road to plenty? Why is China, the world’s most populous country (almost 1.3 billion), now far ahead of India (second with 1 billion), when merely fifty years ago both nations were about equal in per capita income and more impoverished than most poor African nations today? Is there a roadmap leading to a life of plenty, a set of policies and institutional arrangements that developing nations can adopt to replicate the success of advanced modern economies? An honest answer to this question is disappointing. Economic development organizations like the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and countless scholars who have committed their professional lives to the study of economic growth and development are fully aware of the limited theoretical structure yet pieced together. The heartening news is that while we cannot map out a clear highway to wealth, there are clear road signs to point us in the right direction and away from cliffs.

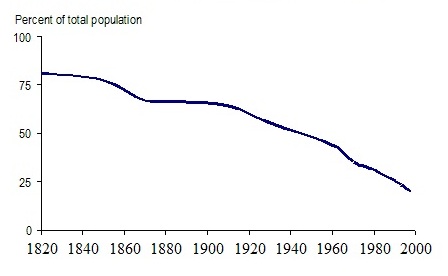

Well known is the fact that a nation’s total output is fundamentally determined (and constrained) by its total inputs, measured in terms of natural resources, labor force, stock of capital, and entrepreneurial talents; and by the productivity of those inputs, measured as the output or service produced per input(s). However, to measure standards of living we rely on output (or income) per capita, rather than total output, and for changes in income per capita, productivity advance dominates the story. For example, if a nation’s population increases by 10 percent, and the labor force and other inputs also increase by 10 percent, output per capita remains essentially unchanged unless productivity increases. Two hundred and fifty years ago, and for many centuries preceding that, most people (80-90 percent of the labor force) everywhere were engaged in agriculture, with much of it being subsistence, self-sufficient, noncommercial farming. Today that proportion is under 5 percent in most advanced economies (3% in the U.S.). During this two-and-one-half century transition, people grew bigger, ate more, and worked fewer hours and days in greater safety and comfort.6 The sources of productivity advance that have raised output per farmer (and per acre) and allowed sons and daughters of farming people to move into other (commercial) employments and careers and into cities include advances or improvements in:

- technology (knowledge);

- specialization and division of labor;

- economies of scale;

- organization and resource allocation; and

- human capital (education and health).

These determinants are especially useful when analyzing the rates and sources of economic growth for single nations, but less satisfactory in explaining why productivity advances and resource reallocations have been so apparent and successful in some parts of the world but not in others.

To explain why some nations grow faster than others, we need to look closely at the way nations apply and adapt these sources of productivity change. To use this perspective, we need to assess the complex relationships of the laws, rules, and customs of a society and its economic performance (North, 2005). For example, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the difficulties of building market-based economies there have made us acutely aware of the importance of the rules of economic and social interaction. Likewise, in Afghanistan and Iraq, we are continually reminded of both the difficulty and the necessity of gaining popular acceptance of changes designed to promote peaceful exchange and economic growth.

Consider just one of the sources of productivity change – technological change—and how it is intimately tied to the institutions, the laws, rules, and customs of a society. A new technology can introduce a whole new product and service, such as the airplane and faster travel, or it can upgrade and improve an existing one; we have come a long way from the 1930’s Model A Fords to today’s luxury BMWs and state-of-the-art hybrid fuel technologies. A new technology can also affect the cost of production; the introduction of relatively light but strong aluminum changed the cost of producing a whole range of goods and services, from soft-drink cans to airplanes.

In short, technological changes can be thought of as advances of knowledge that raise or improve output or lower costs. They often encompass both invention and/or modifications of new discoveries, called innovation. Both require basic scientific research, then further trial and error and study to adapt and modify the initial discoveries and put them to practical use. The inventor or company pursuing research bears substantial risk and cost—including the possibility of failure and no commercial gain. How are scientists, inventors, entrepreneurs, and others encouraged to pursue high-cost, high-risk research ventures? How are these ventures coordinated and moved along the discovery/adaptation/improvement path into commercially useful applications for our personal welfare?

This is where laws and rules, or institutions as they are called, help us better understand the causes of technological change. They establish, positively or negatively, the incentives to invent and innovate. Patent laws, first introduced in 1789 in the U.S. Constitution, provided property rights and exclusive ownership to inventors for their patented inventions. This path breaking law ultimately spurred creative and inventive activity, albeit not immediately. As legal interpretations extended exclusive ownership rights to ideas including the right to sell, a market for new, patented ideas emerged, with inventors often selling their patents to people who specialized in finding commercial uses of new inventions. The keys here are the laws and rules, the institutions, that lay out the incentive structures that generate dynamic forces for progress in some societies and stifle creativity and enterprise in others. In advanced economies, laws provide positive incentives to spur enterprise and help forge markets using commercial, legal, and property rights systems which allow new scientific breakthroughs (technologies) to realize their full commercial-social potential. Properly constructed institutions generate productivity advances through specialization and division of labor, allowing universities, other scientific research institutions, corporations, and other business entities (and lawyers and courts, too) to cooperate through interrelated markets (production and exchange) hastening the growth and spread of technological advances (for elaboration, see Rosenberg and Birdzell, 1986, and Mokyr, 1990).

Getting the institutions right and sustaining institutional changes that realize gains for society as a whole are fundamental to the story of growth. The ideologies and rules of the game that form and enforce contracts (in exchange), protect and set limits on the use of property, and influence people’s incentives in work, creativity, and exchange are the key institutional components paving the road out of poverty.

Examining the successful economies of Europe, North America, and Asia suggests a partial list of the institutional determinants that allow modern economies to flourish:

- the rule of law, coupled with limited government, and open political participation;

- rights to private property that are clearly defined and consistently enforced;

- open, competitive markets with freedom of entry and exit, widespread access to capital and information, low transaction costs, mobile resource inputs, and reliable contract enforcement; and

- an atmosphere of individual freedom in which education and health are accessible and valued. (For advances in education levels see Appendix 1, below.)

North’s study of economic progress confirms that “it is adaptive rather than allocative efficiency which is the key to long-term growth” (North, 1994). The ability or inability to access, adapt, and apply new technologies and the other sources of productivity advances is fundamentally determined by a society’s institutions. Institutions can open doors of opportunity or throw up road blocks. In addition, institutional changes often come slowly (customs, values, laws, and constitutions evolve), and established power centers and special vested interests and religious beliefs sometimes deter and delay changes conducive to economic progress. How accepting is a society of risk and change when change creates losers as well as winners (Shumpeter, 1934), or transgresses religious beliefs?

The Decline of Poverty: Contemporary Trends

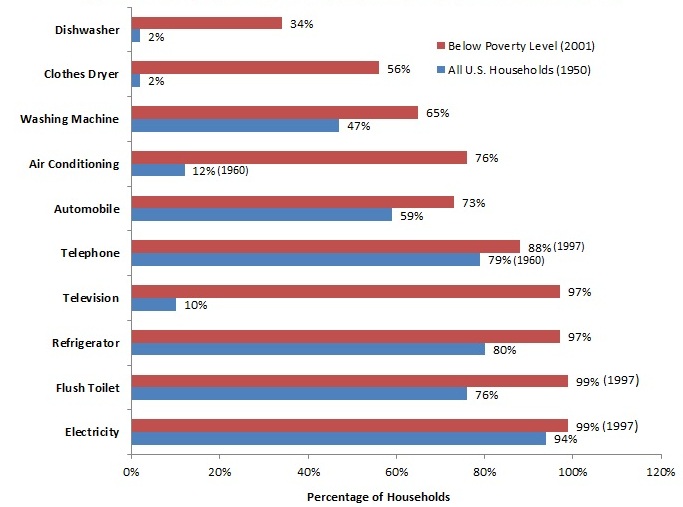

Despite various impediments to positive institutional change in many nations, heightened competition spurred by the information revolution and spread of political and economic participation worldwide bode well for people previously cut off from the path out of poverty. In this regard, it is important to emphasize that economic growth, where it has taken hold, has benefited all layers of society. In the U.S., the rise in material affluence was so great and widespread in the twentieth century that individuals the government currently labels “officially poor” have incomes surpassing those of average Americans in 1950 and all but the richest (top 5 percent) in 1900. The poverty income level in the United States, about one fourth the U.S. average, is far higher than average per capita incomes in most of the rest of the world. To show how widespread the gains from economic growth have been, Figure 2 lists items owned or used by average households in the United States in 1950 compared to below poverty threshold Americans today. Air-conditioned homes with electricity, a refrigerator, a flush toilet, television and telephones are common even among poor Americans. Indeed, American households listed below the poverty level today are more likely to own a color television set than an average household in Italy, France or Germany. In short, the substantial gap among income classes as measured by income and especially wealth becomes much narrower when measured by basic categories: food, housing, and items and services for comfort and entertainment. In the United States there are more radios owned than ears to listen to them.

Figure 2.

Ownership of Poor Households (1997) versus Ownership of All U.S. Households (1950)

Sources: U.S. Bureau of the Census, American Housing Survey for the United States in 1997; U.S. Bureau of the Census, “Housing Then and Now,” www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/census/histcensushsg.html; and Historical Statistics of the United States, Series Q 175.

Figure 3. Amenities in Poor Households

Lest the relative wealth of the American poor seem an exception, it is important to note that the path out of poverty is now being traveled by greater and greater proportions of the world’s population. While the $1 per day (current real purchasing power) threshold value, used by economists and other development specialists as an absolute standard of extreme poverty, is in sharp contrast to the relative wealth of America’s poor, it should not distract us from the reality that poverty in the world is declining. Figure 4 shows that the share of the world population living in extreme poverty – that is, below the $1 per day threshold – has been falling for almost two centuries. The long decline pictured in Figure 4 bears the good news that the battle against poverty made headway even as world population grew. Figure 5 shows that in recent decades the decline in proportion has finally led to a decline in absolute numbers. There were fewer poor people in the world in 2000 than in 1980.

Figure 4. Share of world population in poverty, 1820-1998

Source: Dollar 2003

Figure 5. Number of people living on less than $1 per day, 1820-1998

Source: “Globalisation, Growth and Poverty” by David Dollar and Paul Collier, World Bank, 2001; The Economist 6/28/03.

Recent declines in the number of the world’s poor are primarily a result of institutional improvements in Asia, especially in China and India. Since 1980, more than 200 million people have moved above the poverty threshold measure. The policy shifts allowing private holdings of land in China and greater freedom to create commercial enterprises to produce and exchange goods are revolutionizing life there. These changes were formally institutionalized in 2004 by constitutional changes bolstering private property rights and again in 2007. In contrast, the number of poor people in Africa continues to grow, as insecure property rights and weak regimes of law and order discourage investment, production, and exchange throughout much of the continent.

Remarkably, this absolute decline in poverty, beginning in 1980, has continued right on through the worldwide recession of 2008. The World Bank’s Development Research Group, using $1.25 (2005 real values) as the poverty line, estimates a decline of more than 100 million people as poor, 2005 and 2008. In 1990 the United Nations set a “millennium development goal” of halving world poverty by 2015. That goal was met in 2010 (The Economist, March 3, 2012, p. 81).

Conclusions

Recent declines in the number of the world’s poor are primarily a result of institutional improvements in Asia, especially in China and India. The policy shifts allowing private holdings of land in China and greater freedom to create commercial enterprises to produce and exchange goods are revolutionizing life there. These changes were formally institutionalized in 2004 by constitutional changes bolstering private property rights and again in 2007. In contrast, the number of poor people in Africa continues to grow, as insecure property rights and weak regimes of law and order discourage investment, production, and exchange throughout much of the continent.

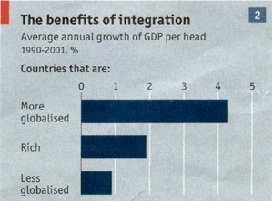

Evidence on the economic growth effects of expansive markets and integration into world exchange is given in Figure 6 which shows the phenomenal growth rate of economies that have moved away from centrally-planned, closed economic systems, to open, globally integrated systems. (See Appendix 2, below, for a static ranking of countries by measures of openness to international trade.) The comparison to both advanced rich nations and to those which, by design or lack of opportunity, have not globalized is striking. The faster growth rates of nations entering into the world market system is positive news, holding out the very real possibility of poorer nations “catching up” to the material comforts enjoyed by the advanced/rich nations, even as the less globalized fall farther behind.

Figure 6. Benefits of Integration

Sources: “Globalisation, Growth and Poverty” by David Dollar and Paul Collier, World Bank, 2001; The Economist 6/28/03

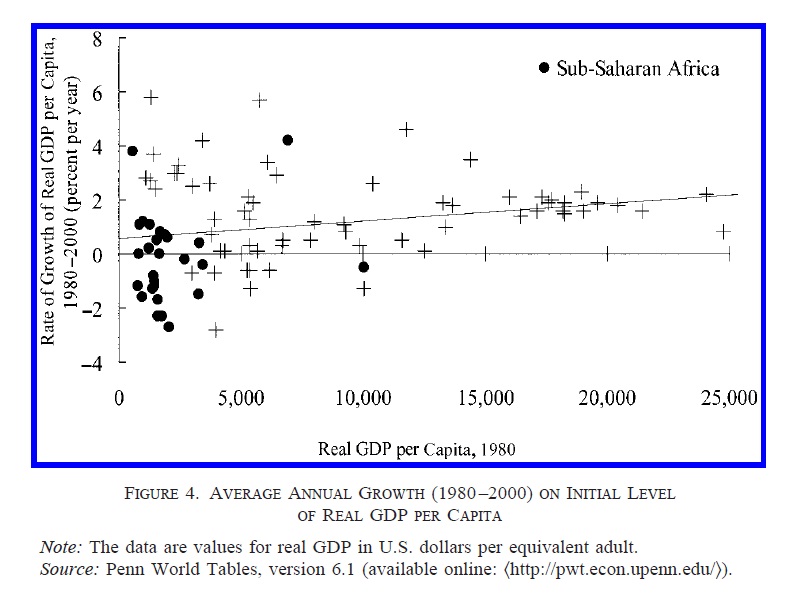

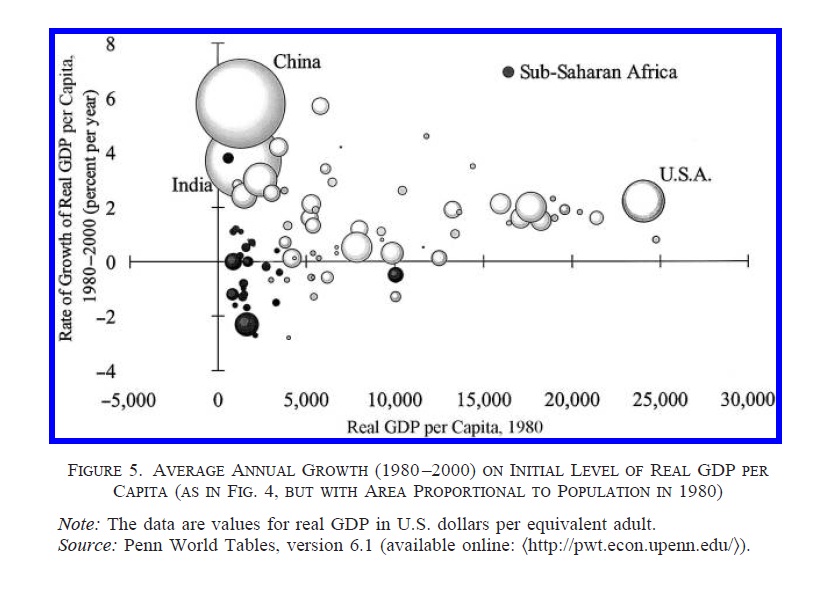

This positive conclusion requires elaboration because it rests on both actual growth rates and population size. From the work of Stanley Fisher (2003), we can see the growth rates of nations in Figure 7, unaccounted for population size. The upward trend line shows richer nations growing more rapidly on average than poorer nations. Figure 8, however, magnifies the dots according to population size, revealing a downward trend, a catching up. Especially in Asia, where institutional economic change has been notable, populous China and now India are following Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea out of poverty. This catching up process is in sharp contrast to the white dot representing sub-Saharan Africa. Africa is the great institutional challenge of the 21st Century.

Figure 7. Growth in GDP per head

Figure 8. Growth in GDP per head, proportional to population 1980

Source: See Fisher, 2003.

Recent research by Haber, North and Weingast emphasizes this point especially with regard to political institutions in Africa.

Economists have made an impressive start on the types of economic institutions needed to support efficient markets, but have not made equal strides in devising political institutions that will accomplish that objective. It took a Sekou Touré, or a Hastings Banda, five minutes of despotism to undo the finest economic theory…

…In effect, solving the development problem in Africa requires the crafting of political institutions that limit the discretion and authority of government and, more saliently, of individual actors within the government. No simple recipe for limiting government exists. (The Wall Street Journal, July 30, 2003)7

Devising political systems that divide power, either (1) by checks and balances among branches or components of one level of government; or (2) by federalism creating competition among layers of government, holds promise for the needed economic institutional support of enterprise and markets. The daunting challenge for poor nations is to craft better political institutions and to promote the rule of law, rather than the more arbitrary rule of men (North, et al., 2007). This challenging transition is vital because “history offers us no case of a well-developed market system that was not embedded in a well-developed political system” .8(see footnote 7 and “A Survey of Sub-Saharan Africa,” The Economist, January 17, 2004).

Regardless of the fact that some areas of the world are still struggling (and failing in some cases) to move onto and along the road out of poverty by getting the institutions right, greater and greater numbers of humans are living longer, in greater ease and comfort, and with more dignity. It is noteworthy that two hundred years ago, scholars, most notably Malthus, were preoccupied with the challenge of feeding the poor, while in advanced countries today the main challenges are fighting obesity and caring for the aged. Although revolutions, natural and man-made catastrophes, and war can imperil regions, the economic evidence and historical record provide ample reason to expect that the global progress launched by open markets and individual freedoms secured by rule of law around 1750 will continue indefinitely. The creative powers inherent in secure, stable, competitive, open-market systems are the well-spring for optimism about the future of mankind.

Footnotes

1 Such glorification has a long tradition: ” The humour of blaming the present, and admiring the past, is strongly rooted in human nature, and has an influence even on persons endued with the profoundest judgment and most extensive learning,” from David Hume, ‘Of the Populousness of Ancient Nations,’ in 1777/1987, 464.

2 For example, see Winston Churchill’s description of life in Britain during and after the Roman Era (Churchill, 1956, Vol 1).

3 A long but much shorter timeline from the first appearance of Homo sapiens to now can be seen on www.archaeologyinfo.com/species.htm. For additional demarcations see Diamond, 1999, Ch. 1.

4 For a sober reflection on the hundred most important people ever, and their inventions, creations, and achievements, see Hart, 1994.

5 Minimum daily energy requirements (citations in Goklany, p. 37) to engage in light work and maintain body weight and health require between 1720 and 1960 calories per day. Per capita estimates, of 1750 for France in 1790, and of 2060 in England, are well over 3000 today. 1950 averages of 1635 in India, and of 2115 in China, compare to 2466 and 2972 in 1998 (Goklany 2001, p. 5).

6 For the dramatic growth of human time available for leisure and other (non-work) discretionary uses since 1880 see Fogel, 2004, Ch. 4.

7 Haber, Stephen, North, Douglass C., and Weingast, Barry R. “If Economists Are So Smart, Why Is Africa So Poor?” Wall St. Journal (July 30, 2003).

8 And yet there is recent good news even for Sub-Saharan Africa, where the steady rise of poverty there, 1981-2005 shifted to declines since 2005. (The Economist, March 12, 2012, 81-2).

Selected References and Suggested Readings

Burnette, Joyce and Joel Mokyr. “The Standard of Living Through the Ages.” In The State of Humanity, ed. Julian L. Simon. (1995): 135-148.

Barro, Robert J. and Jong-Wha Lee. “A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950-2010.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 15902. April, 2010.

Churchill, Winston S. A History of the English Speaking People. Vols 1-4. New York, Dorset Press, 1956.

Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999.

Dollar, David. (consignment research paper for the Foundation for Teaching Economics, Davis, California, 2003).

Fisher, Stanley, “Globalization and Its Challenges, American Economic Review, 93, 2, May 2003, pp.1-30.

Fogel, Robert W. “Economic Growth, Population Theory, and Physiology: The Bearing of Long-Term Processes on the Making of Economic Policy.” The American Economic Review, 84, (1994): 369-395.

Fogel, Robert W. “Catching Up with the Economy.” The American Economic Review, 89, (1999): 1-21.

Fogel, Robert W. Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, 1700-2100. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Goklany, Indur M. “Economic Growth and the State of Humanity.” PERC Policy Series, April 2001.

Haines, Michael R. “Disease and Health through the Ages.” In The State of Humanity, ed. Julian L. Simon. (1995): 51-60.

Harberger, Arnold C. “A Vision of the Growth Process.” The American Economic Review, 88, (1998): 1-32.

Hart, Michael H. The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History. New York: Citadel Press, 1994.

Maddison, Angus. Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992. Paris: Development Centre of the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 1995, 23-4; http://new.sourceoecd.org/vl=8588901/cl=23/nw=1/rpsv/cgi-bin/fulltextew.pl?prpsv=/ij/oecdthemes/99980010/v2003n16/s1/p1l.idx (May, 2006)

Maddison, Angus. World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2003 AD, 2006, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/ (May, 2006)

Mokyr, Joel The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress, New York, Oxford University Press, 1990.

Murray, Charles. Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. – 1950. New York: Harper Collins, 2003

North, Douglass C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

North, Douglass C. “Economic Performance Through Time.” The American Economic Review, 84, (1994): 359-368.

North, Douglass C. Understanding the Process of Economic Change. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

North, Douglass C., John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework of Interpreting Recorded Human History. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Preston, S.H., “Human Mortality throughout History and Prehistory,” In The State of Humanity, ed. Julian L. Simon, 1995.

Rosenberg, Nathan, and L.E. Birdzell, Jr. How the West Grew Rich. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1986.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. The theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1934.

United Nations Development Program. 1999. Human Development Report 1999. New York: Oxford University Press.

World Resources Institute. 1998. World Resources 1998-99 Database. Washington DC.

Wrigley, E.A., and R.S. Schofield. 1981. The Population History of England, 1541-1871: A Reconstruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Appendix 1:

Education, Average Number of Years for Adults Over 15 Years of Age. (1950 – 2010)

Area 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 World 3.17 3.65 4.45 5.29 6.09 6.98 7.76 Advanced 6.22 6.8 7.74 8.82 9.56 10.65 11.03 Developing 2.05 2.55 3.39 4.28 5.22 6.15 7.09 Sources: Barro et al., 2010

Appendix 2:

Rankings of Nations from Least to Most Globalized, 2005

LEAST GLOBALIZED I II III IV 60 Kenya 45 Greece 30 Panama 15 Belgium 59 South Africa 44 Uganda 29 Spain 14 Austria 58 Peru 43 Chile 28 Japan 13 Australia 57 Nigeria 42 Ukraine 27 Bulgaria 12 Britain 56 Sri Lanka 41 Poland 26 Croatia 11 Sweden 55 Egypt 40 Morocco 25 France 10 Estonia 54 Argentina 39 Costa Rica 24 Hungary 9 Jordan 53 Thailand 38 Philippines 23 Malaysia 8 Canada 52 Saudi Arabia 37 Taiwan 22 Germany 7 United States 51 Senegal 36 Romania 21 Israel 6 Denmark 50 Columbia 35 South Korea 20 Slovenia 5 Ireland 49 Mexico 34 Italy 19 Czech Republic 4 Switzerland 48 Vietnam 33 Ghana 18 Finland 3 Netherlands 47 Botswana 32 Slovakia 17 Norway 2 Hong Kong 46 Tunisia 31 Portugal 16 New Zealand 1 Singapore MOST GLOBALIZED

Source: ATKEARNEY, 2007. http://www.atkearney.com/images/global/pdf/GIndex_2007.pdf

Debbie Henney, FTE Director of Curriculum Receives Bessie B Moore Service Award

Foundation for Teaching Economics is proud to announce that Debbie Henney, director of curriculum for the Foundation for Teaching…

FTE Pays Tribute to Jerry Hume

It is with deep sadness that we announce the loss of William J. Hume, known as Jerry Hume, former Chairman…

Why We Should Be Teaching Students Economic Literacy

Ted Tucker, Executive Director, Foundation for Teaching Economics October 26, 2022 More high schools are offering courses on personal finance…